Beginner's mind: seeing the mathematics

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: January 22, 2010

My colleague has a Ph.D. in mathematics and two young children – 9 and 11 years of age.

She writes the following account of her children’s engagement with a word problem:

Yesterday my 9 year old was struggling with the following problem:

“Suzi and Joey had the same amount of money. Then they went shopping. Suzi spent $18 and Joey spent $25. When they were done, Suzi had double the amount of money Joey had. How much money did Joey have left?”

Another, helpful, adult was trying to assist him, introducing all kinds of X’s into the problem. While he now understood the answer, he didn’t understand why it worked that way. So they came to ask me to explain it.

I looked at the problem and formulated it in my mind:

2X+18 = X+25

so X=7.

Before starting to explain the problem, I restated it.

My 11 year old son, who was reading nearby, immediately said “7”.

I asked him why, and he explained that that was the amount that Joey spent more than Suzi, and that is half the amount that Suzi had left.

It seemed very obvious to him: he just “saw” it.

I must admit (shame-faced) that it was not all that obvious to me until he explained it. I was thinking of the problem procedurally, whereas he immediately saw the relationships between the numbers. In Skemp’s terms, I, the expert, was thinking instrumentally, and he, the beginner, was thinking relationally.

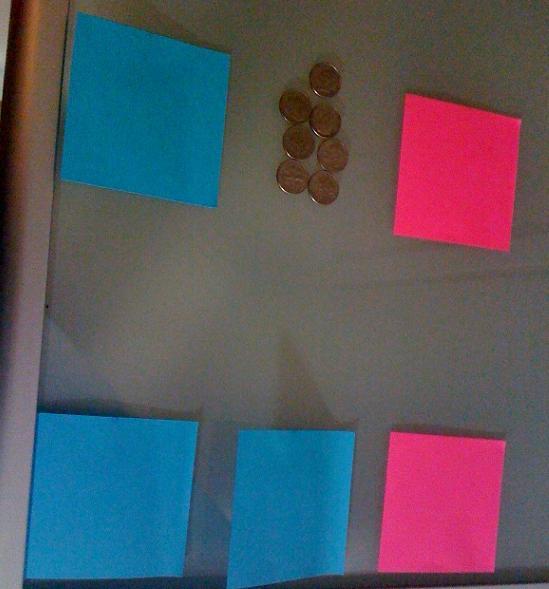

Now to explain it to my 9-year old, I used the tools on my desk.

First I took a turquoise post-it note and 25 coins and put it on one side, and 2 turquoise post-it notes and 18 coins on the other side.

I grouped the 25 coins into 18 and 7. Now it was obvious that on the two sides on the desk, the 18 coins on each side paired up (i.e were equal), a turquoise post-it on each side had a pair on the other side, and the remaining seven must then be equal to the second turquoise post-it.

To abstract it a little more, I replaced the 18 coins on each side by a pink post-it.

This was to represent that it really doesn’t matter HOW MUCH money each spent, but only the difference between the two.

Now, of course, it was “obvious”, even to a mathematician with a Ph. D.

So I have 2 questions:

1. How do we train someone to see this problem relationally and not procedurally and instrumentally?

And, more critically:

2. How do I make sure not to ruin the understanding my 11-year old has, when teaching him to do this procedurally?

How about infinity plus one?

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: January 21, 2010

Corina Silveira came from Argentina to carry out research for her doctorate in mathematics education at the University of Southampton in England.

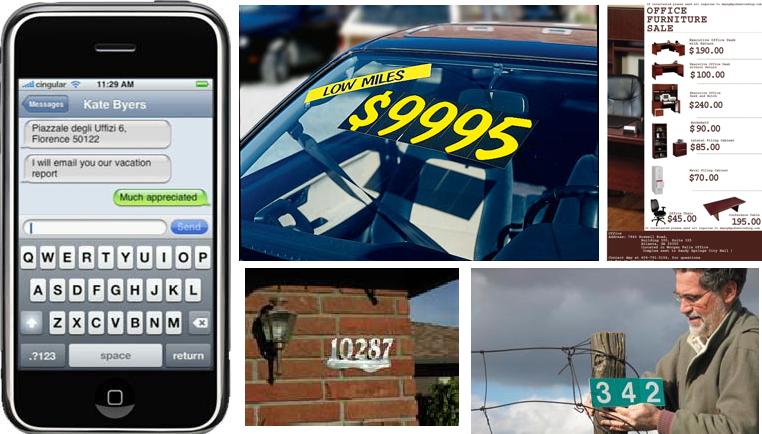

Corina was interested in how children developed an informal sense of number through their world experiences – particularly seeing adults deal with prices of goods and vehicles, and seeing telephone numbers, street numbers, and such.

She had worked in Argentina on mismatches between children’s developing sense of numbers out of school, and the more structured work they did in school usually with much smaller numbers – typically up to 20 in the first semester or school term.

Corina was interested to map out a picture of the development of children’s everyday number sense, and its relationship to known development in counting.

We found a school in South Wonston, north of Southampton, where a grade 1 teacher and her students were happy to work with us.

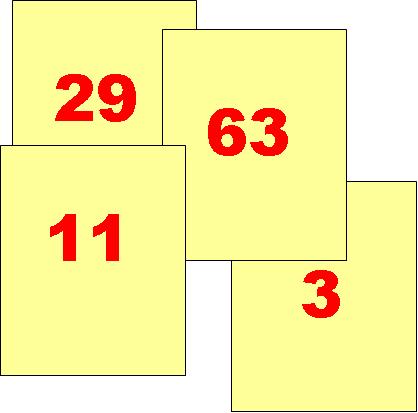

Among other things, Corina devised a game for about 4 children in which each child was dealt a small number of cards, each of which had a (different) number from 1 through 100.

Children took turns in placing a card on the table and a hand was won by the child who put down the largest numbered card.

There is an element of strategy in this game in that if a card on the table is higher than all your cards then you should play your lowest card.

Corina was interested in an answer to the question: how do these 5 year old children know which is the largest number?

A few times the card with “100” on it was dealt, and each time that happened the child who got the card started laughing. One boy laughed so hard he fell backwards onto the floor, crying out: “Oh, oh! It’s the biggest one of all!”

Corina asked a group of children how they knew 63, on a card, was bigger than 29, as they said it was.

One child pointed to the card with 63 and said:

“Because it’s got a 6.”

When Corina objected that the other card had a 9, the children jostled to tell her, with almost pity in their eyes that an adult would not know such a thing:

“But the left hand’s the boss!”.

These children could not read 69, but knew that the left hand 6 meant it was a bigger number than 29.

Among the children in this first grade was a boy named Tom. He was somewhat developmentally delayed, having relatively poor coordination, and being slow at both counting and reading. Â Tom had arrived at the school the year before and was, by his teacher’s account, not well socialized at that point.

Now, however, Tom was very keen to join in the card game. He told us very proudly that he was a good counter.

“Would you like me to count for you?” he asked.

Of course we agreed . So he counted:

“One, two, three, four, five, seven, eleven, twenty, thirty!”

He beamed.

“I’m a good counter. I practice at home.”

That was Tom: happy to be in school, happy to be part of his grade of school mates, happy to be learning to read and count.

It is common in England for children to be placed in groups, or sets, according to their general academic ability. Tom was in the bottom set.

The top set in Tom’s grade 1 consisted of 4 boys who were keen to know why we were in their classroom.

I explained that we were interested in what they knew about big numbers, such as one hundred, one thousand or even one million.

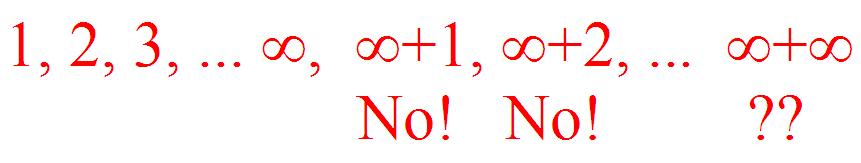

One of these top set boys said to me:

“I will tell you what’s the biggest number there is.”

“The biggest number there is?” I queried.

“Yes. It’s called infinity.”

“Infinity?” I repeated.

“Yes, it’s the biggest number there is.”

I nodded, looked him in the eye, and said:

“Infinity plus one.”

“No, no, no”, he said. “You can’t do that … cause infinity is the biggest number.”

Another of the boys chimed in with: “Infinity plus two!”

No, no!” said the first boy. “You can’t do that…”

Then the last boy in the group looked at us all and said:

“Infinity plus infinity!”

All the boys looked at each other, and at me, apparently wondering if this might make some sense.

The teacher in this grade 1 class was wonderful. Friendly, supportive, with as challenging activities for each group as she could find or devise. She taught them reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, social studies, science and who knows what else.

Yet how could this excellent teacher deal individually in mathematics – grade 1 mathematics – with Tom who could not yet confidently and reliably count to 10, and the top set boys who were pondering infinities?

Corina and I found 4 and 5 year olds who knew confidently that there would be no house in their street numbered 1024 because they lived in a very short street, or who knew that 2,500 was a large number because that’s what someone’s mother paid for her car. We also found children who knew that the number on their house was the same as the number on their trash bin, but did not know why.

Kids learn about numbers by learning to count. Â They also learn about them as artifacts in the adult world. Â In the early years of schooling teachers generally stick to counting up to small numbers. But the children have another sense of number and magnitude and meaning that comes from the way numbers are used in the world outside of school.

Only by listening to their stories will we know what they know, and how we can help advance their knowledge and thinking. Kids need listening to as much as they need teaching.