A little bit of generating-function-ology

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: April 2, 2011

James Tanton (@jamestanton) raised the interesting question of what numbers we get if we from the infinite decimals

James Tanton (@jamestanton) raised the interesting question of what numbers we get if we from the infinite decimals and

Here we are placing the numbers and

in the

digit place in the infinite decimals.

This means that we will have to perform a lot of carries to figure out what these numbers are.

Or does it?

What James Tanton is asking us to calculate are the numbers and

By combining two ideas of Isaac newton – calculus and power series – we can, relatively easily, calculate these numbers, and more.

They are in fact rational numbers – fractions.

Curiously, Isaac Newton thought of power series as generalizations of decimal numbers where we expand a number using the digits and powers of

.

We will do just the reverse.

Let’s denote the infinite sum , where

is a positive integer, by

.

We will treat as a formal power series to be manipulated term-by-term, but will interpret it as a number when

is chosen appropriately – mainly as

.

The formal derivative, of

, is the infinite sum

x

When we multiply by

we get the infinite sum

That is, .

Now we can fairly easily figure out

That’s because if then

so and

.

In particular,

This allows us also to calculate

In particular,

We can continue this way to calculate for higher values of

.

For example so

One thing we notice is that we always get a power of 9 in the denominator.

Of course a 3 in the numerator might cancel a 3 in the denominator, so we can say that in reduced form will have a denominator that is a power of 3.

Geometry and the built environment

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: April 1, 2011

Geometric terms

Geometric terms

Students often forget geometric language they learned in earlier grades

The meaning – precise or vague – of words such as parallelogram, rhombus, angle bisector, acute angle, escape them.

They have not learned to talk “geometry”.

But the language is only a small part of the issue.

Much harder is that their teacher is almost certainly thinking about geometry in ways they cannot imagine: they cannot know what they do not know.

For example, students whose geometric thinking is at a beginning level might describe objects as “round” or pointy”

An object such as the following might be described as “long and thin”:

A teacher, on the other hand, is more likely to know a name: “rectangle” and to know properties: opposite sides same length and parallel, all angles right angles.

A teacher might also know relationships between properties: having opposite sides parallel and of the same length does not mean all angles are right angles:

Simply pointing out properties and relationships between them is not going to help a student reach that level of understanding.

Talking “geometry” like this one might as well be talking Hindi.

The student at a lower level of development is simply not going to understand the words or their intent.

van Hiele levels

This IS a developmental issue, and the two people who began the study of development of geometric thinking in students are Dina van Hiele-Geldof and Pierre van Hiele.

Their theory of the development of geometric thinking is known as the van Hiele model.

This model, which has been the subject of much empirical justification, posits several broad “stages” of development in geometric thinking.

Like all stage or level theories of development, the van Hiele model is flawed in that students show signs of one level and then regress, particularly as they are in transition from one broad level to another.

The van Hiele levels are static descriptions and so not capture the dynamic transitions students make as they are learning.

Yet if a teacher of geometry does not understand these levels of geometric thinking and has not found out where their students lie in relation to these levels, they are going to have a frustratingly difficult time teaching their students geometry.

Geometry of the built environment

One way for a teacher to address where their students might be in relation to the van Hiele levels is to get students to take pictures of geometric objects in the built environment.

Students can use cell phones to take pictures as they are out and about, at home, in shopping centers, in the street, at recreational areas, for example.

Students could upload their images to a WordPress blog, or other Web page set up by the teacher.

Students could write a few words describing their images and talk briefly to them in class.

This way a teacher can get an approximate understanding of where a student’s geometric thinking is in relation to the van Hiele levels.

That makes it easier for the teacher to adjust activities for a given student on the basis of what the teacher knows about how the student is currently thinking.

Kids will usually get quite motivated to find better and more interesting geometric images from the built environment.

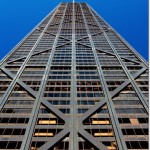

Here’s a truly spectacular example:

When their interest peaks, and begins to wane, there’s always the natural environment.

Some pointers to the literature

Burger. W. F. (1986) and Shaughnessy, J. M. (1986) Characterising the Van Hiele levels of development in geometry. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 17, 31-48.

De Villiers, M. D. and Njisane, R. M. (1987) The Development of geometric thinking among black high school pupils in Kwazulu (Republic of South Africa). J.C. Bergeron, N. Herscovics & C. Kieren (Eds.) Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Vol 3, pp. 117-123. Montreal.

Fuys, D., Geddes, D., Lovett, C. J. & Tischler, R. (1988) The Van thinking in geometry among adolescents. Journal for Research in Education [monograph number 3]. Reston, VA: NCTM.

Mayberry, J. (1983) The Van Hiele levels of geometric thought in pre-service teachers. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 14(1), 58-69.

Orton, R. E. (1995) Do Van Hiele and Piaget belong to the same research? Zentralblatt für Didaktiek der Mathematik, 27, 134-137.

Presmeg, N. (1991) Applying Van Hiele’s theory in senior primary geometry: phases between the levels. Pythagoras, 26, 9-11.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1986) On having and using geometric knowledge. In James Hiebert(Ed.), Conceptual and procedural knowledge: The case of mathematics. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Senk, S. L. (1989) Van Hiele levels and achievement in writing geometry proofs . Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 20, 309-321.

Usiskin, Z. (1982) Van Hiele levels and achievement in secondary school geometry. University of Chicago Van_Hiele_Levels_Usiskin