Transformative mathematics education: 14 indicators of success

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: October 20, 2010

Carolyn Foote, High School educator and “techno-librarian”, has an excellent article at The Huffington Post. Let me paraphrase her:

“Transformative school change needs to take a hard look at what really moves our students towards a “21st century (mathematics) education” — an education where students are working on inquiry-based, real world problems, and acknowledge the connected world they live in, where they can connect and learn globally, and where thinking and problem solving are valued over the memorization of (mathematical) facts and figures because they live in a Google-able world.”

Carolyn is talking about education in general, yet her words strike a deep chord with me in relation to the teaching and learning of mathematics K-20.

The work that my colleagues and I do in educating undergraduate mathematics students about computational mathematics is transformational for many – but not all- of those students.

x

x

It’s relatively easy to provide indicators of transformation:

- the desire a student shows to discuss their work both in and out of class,

- the depth and quality of their writing,

- their desire to hear from outside experts,

- their need for equipment and materials to pursue their project,

- the number of different projects with which they become engaged,

- the number of different students with whom they engage,

- the questions they ask of other students,

- the assistance they give to other students,

- the assistance they ask from other students,

- the breadth and depth of new mathematics and skills they desire to learn,

- the new employment opportunities they see,

- their desire for continuing education,

- coming to their teachers with new ideas for projects,

- forming clubs and societies dedicated to their mathematical work,

among other things.

These indicators are part of our method of assessment, yet they are not refined, or always easily quantifiable indicators. If someone asks why students earned an A in this course, we usually point to their ongoing and final written reports. Yet the other indicators tell us a lot about whether we are making a transformational impact on a student. Do they see see career opportunities that they did not before? Are they excited about particular subjects? About meeting up with local, national and international experts? Are they forming clubs and societies dedicated to their mathematical work? Are they coming to their teachers with new ideas for projects?

Carolyn Foote’s call for a 21st century transformative education is vitally important, in my view. I am sure it is important across the board in education. I know it is critical in mathematics education if we are to move away from the stultifying engagement with dull, routine exercises that commonly passes for mathematics education. It is critical if Paul Lockhart is to obtain relief from his, sadly eloquent, lament:Paul_Lockhart_A_Mathematician’s_Lament

I would dearly like to hear from other mathematics educators about their thoughts and efforts in providing transformative education for their students. If someone would like to write a guest post I am delighted to hear about it, and happy to provide the space and opportunity.

Check your answer: Building mathematical muscles

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: October 18, 2010

Teachers everywhere have to pay more attention to learning outcomes. Sometimes these outcomes are very specific to certain courses, even sequences of lessons, and other times they are more generic. One generic outcome that is valued by most teachers of mathematics is a demonstrated ability of, and propensity for, students to check their answers.

Teachers everywhere have to pay more attention to learning outcomes. Sometimes these outcomes are very specific to certain courses, even sequences of lessons, and other times they are more generic. One generic outcome that is valued by most teachers of mathematics is a demonstrated ability of, and propensity for, students to check their answers.

What is behind “check your answer” is that students, of any age, should progressively become more independent learners, capable of knowing if their answers are correct.

Students need to build progressively stronger mathematical muscles.

This learning outcome was brought to mind strongly for me when I read the following review of the book The Magic of Numbers by Benedict Gross & Joe Harris:

This book is VERY readable — and easily approachable — BUT, suffers from a major defect for the SELF-LEARNER. There are *tons* of exercises that are recommended — which would be great except doing the exercises is a complete waste of time — you don’t know if you got the exercise right or wrong! Yup. Ok, Now you do it: 1. what’s 2^5 mod 11?, 2. 2^17 mod 23?….etc? Nice BUT if you do the exercises, you don’t know if you got the right answer or not, so its a waste of time.

Worse — the authors emphasize the need to do the exercises — but if you don’t know if you did them right or wrong, what’s the point? There are a fair number of examples that do give answers, but these are about 1/5th – 1/6th the problems and the answers are given in the text of the problem. So while you know the answer, you can’t really do the example, then see if you got the right answer — because it’s also there in front of you.

Having an answer key — even if it was for every even or odd exercise would be helpful. Non-answered questions could be for those classes where the teacher doesn’t trust the student to learn, but just copy answers, but if that’s the case, why bother taking a class? Just copying answers doesn’t help much in the real world nor on exams (which one would presumably have in a classroom setting).

But I bought this book for educational/recreational reading (just like some people like to participate in sports or go to a gym to exercise a body, many find mental exercise equally valuable for one’s “head”).

I would NOT recommend *against* the book, but it may go slowly, as the paucity answered problems make for slower going in terms of comprehension and retention (I find I more often have to reread prior chapter I understood, but didn’t get enough practice to retain in order to progress onto more complex subjects).

For self-learning, FEEDBACK is required — no feedback, then no learning if you are doing it right or wrong, but the format, typesetting, and conversational style on this book make it very readable. Just wish they had the answers (or at least odd numbered answers in the back).

The author of this review is arguing that the exercises in the book have no answers and therefore, adequate learning cannot take place, because that requires feedback, in the form of correct answers.

I feel for the author because it seems they were raised on a diet of textbooks that had answers in the back so that a reader could check if their own answers were correct.

What is wrong with this? Several things. First, the answers in the book might not be correct: sometimes that is the case. Second, taking the book answer as the standard for a correct answer takes the authority for obtaining a correct answer from the student and places it firmly with the author of the book. Thirdly, taking the book answer as correct takes from the learner the possibility of becoming independent by learning how to check if their answer is correct.

Let’s take a look at some examples the review author complains about:

1. what’s 2^5 mod 11?, 2. 2^17 mod 23?….etc?

The section of the book that contains exercises like these is in Chapter 18 on Powers, specifically, in section 18.5 Calculating Powers mod p.

The main tool for calculating powers modulo a prime number is Fermat’s little theorem (p. 199):

If is any prime number and

is any number not divisible by

then

To apply Fermat’s little theorem to the above exercises we observe, for the first exercise, that 11 is prime and 2 is not divisible by 11 so .

This does not seem to be a lot of help right off because we want and Fermat’s theorem tells us about

.

Couldn’t we just calculate directly, and see what the remainder is after division by 11?

and

so

.

This seems simple enough, but if we have been fed a steady diet of “check your answer with the back of the book” we might be feeling nervous because maybe we made a mistake. We aren’t getting feedback. How could we check by giving ourselves feedback?

One thing we could do is to use that fact that . If our calculation of

is correct then

which Fermat’s little theorem says is correct. That’s reassuring.

How might we have made a mistake? Could it be in the calculation of . Not really because we know that

. So if we made a mistake in the calculation of

it could only have been in working out the remainder after

is divided by 11. Since

we see that

so

.

This seems length and drawn out, and to some extent it is for such a simple exercise. Yet it illustrates the benefit obtained from the cost of checking: we now feel much more confident that our answer is correct. If we looked it up in the back of the book we would not be building up our checking muscles, and we would stay that much mathematically weaker.

How about the second exercise the author of the book review mentions: what’s 2^17 mod 23?

Curiously, when I looked through the book I could not find this exercise. What I did find was:

Exercise 18.6.3 Evaluate the power .

Let’s do this exercise first and think about how we might check the correctness of our calculation without looking up an answer in the back of the book.

Using Fermat’s little theorem we see that . This because 23 is a prime number and 2 is not divisible by 23.

How does this help us? We need to relate the power 22 to the power 83. Well, so we use the fact that

to get

.

Now the problem is to calculate . The text just before this exercise gives us a hint to use the method of section 18.2

So now we see maybe where the problem “ what’s 2^17 mod 23?” came from – the author of the review has maybe used Fermat’s little theorem and is stuck on calculating .

One way to proceed is to use that fact, from and 22=17+5, that

is the inverse of

.

We know that from a direct calculation that so we just have to find the inverse of

: in other words solve the equation

. We can try

so

. Then squaring again gives

and therefore

.

This gives us our final answer of .

If this seems long and complicated it is: it’s messy and we could easily have made a mistake. How can we check our answer?

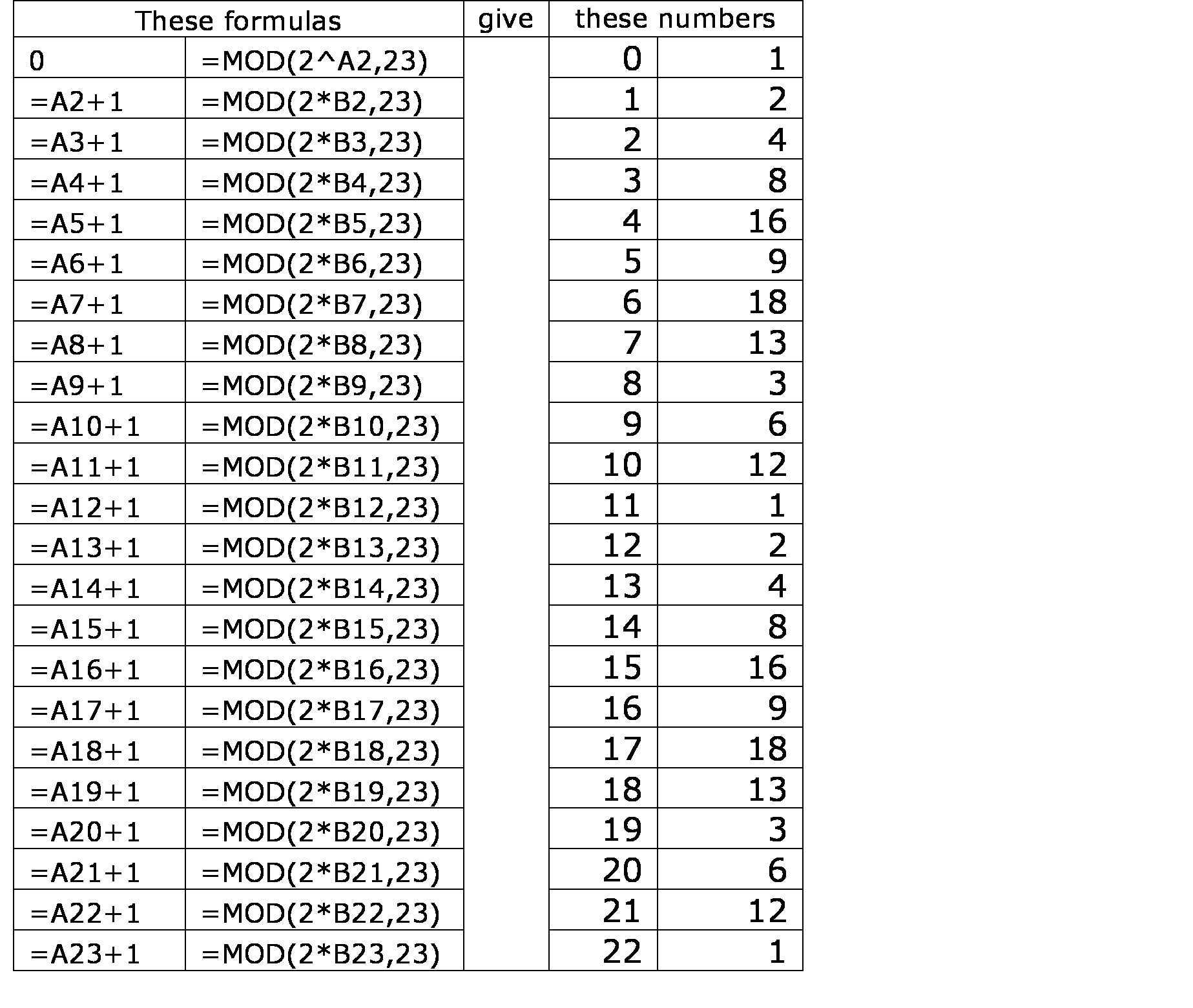

One way is to absorb more fully the lesson of section 18.2 and construct a table of powers of 2 (mod 23) up to the power. We do this starting with

and then multiplying the previous result by 2 and keeping the remainder after division by 23. Here’s is a table built using Excel:

This gives us a much more complete and satisfying feeling than looking up the answer in the back of the book. It helps us build our mathematical muscles, and learn to reason mathematically as an independent thinking person.