What is a triangle? The role of definition

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: October 2, 2010

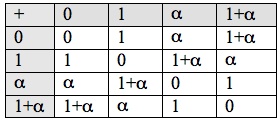

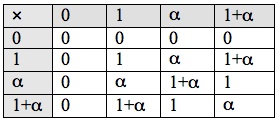

The Galois field of order 4 is the set with addition and multiplication given by the following tables:

Because

Because for every

we see that not only addition and multiplication, but also subtraction is always possible in GF(4), although subtraction is trivial since

.

Also, because we see division, except by 0, is always possible in GF(4). This makes GF(4) an example of a mathematical field, one of the finite fields discovered by Evariste Galois who died at age 20.

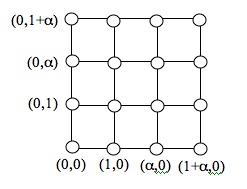

We can use the finite field GF(4) , much as we use the real numbers, to construct a plane , which in this case is a finite plane:

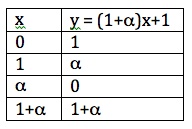

In this plane we can construct a line, much as we can in the Euclidean plane. For example the line

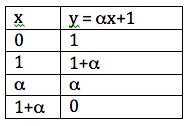

In this plane we can construct a line, much as we can in the Euclidean plane. For example the line contains points as follows:

and so looks like this in the plane :

Now let’s try to build a triangle by producing a line from the point with slope

. This will be a line with equation

passing through the point

, so

. The points on the line

are given as follows:

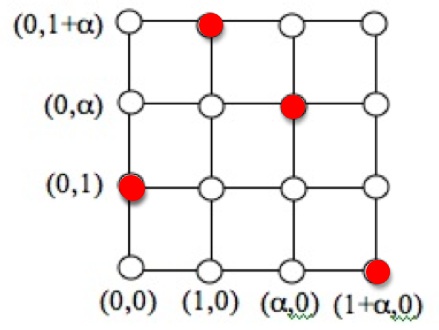

and this looks as follows in the plane

and this looks as follows in the plane (shown with dots):

Now let us complete a triangle by joining the point to the point

by a line. A line which does this has equation

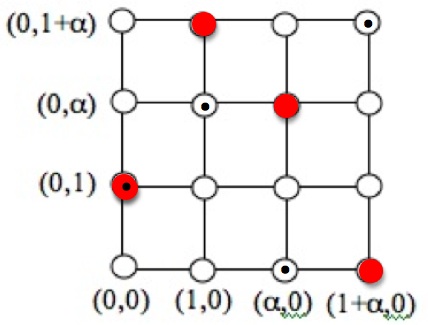

. So filling in all the points on the lines constituting the triangle, we get:

This triangle is determined by 3 lines, each with 4 points. The lines meet at 3 endpoints, leaving two other points on each line to form the triangle.

Such is the nature of mathematicians that they give the same name to different looking, but similarly defined objects. It is the definition, and not the appearance, that determines what sort of object we have.

The understanding of finite fields to construct this simple example, and much, much more, was made possible through the work of the incomparable Evariste Galois.

Cantor's basic idea of infinity plus 1

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: October 1, 2010

Many people do not think it is problematic to bundle all the counting numbers together in a set: the set of all natural numbers. Yet from a set-theory perspective this is an explicit axiom – the axiom of infinity – because the other axioms of what by now are standard set theories allow an interpretation with finite sets only. So we need an explicit axiom to ensure that the natural numbers can form a set. It’s common to denote this set by , and people will get into ferocious, but unenlightening, debates about whether 0 is, or is not, in

. We will assume 0 is not in

and that

begins

.

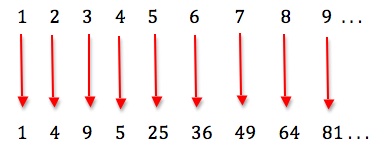

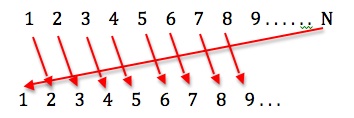

Galileo noticed a peculiar thing about this infinite set of all natural numbers – that it can be placed into one-to-one correspondence with a smaller part of itself:

Galileo reasoned that the squares of whole numbers are themselves whole numbers, but only a part thereof – for example 3 is not the square of a whole number. Yet the squares are matched to all whole numbers by the reverse operation of taking the square root.

Galileo reasoned that the squares of whole numbers are themselves whole numbers, but only a part thereof – for example 3 is not the square of a whole number. Yet the squares are matched to all whole numbers by the reverse operation of taking the square root.

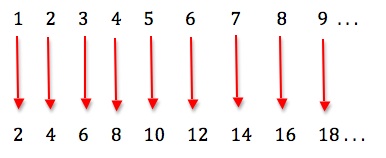

Because one-to-one correspondence is the basis of how we count, to answer the question “How many?”, Galileo’s observation is that there are, from this perspective, just as many squares of whole numbers as there are whole numbers. Similarly, there are just as many even numbers as there are whole numbers:

This is a peculiarity of an infinite set: it can be placed into one-to-one correspondence with a part of itself, quite unlike the situation for finite sets.

This is a peculiarity of an infinite set: it can be placed into one-to-one correspondence with a part of itself, quite unlike the situation for finite sets.

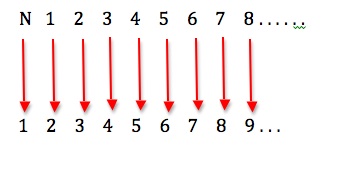

Cantor was aware that even if we were to enlarge the set of natural numbers by putting in a new element, we would essentially still have he same number of elements. What new element could we add to the set ? What about

itself?

![]() We’ve added

We’ve added to the right of all the natural numbers to indicate that we regard this new element as bigger than any natural number.

But still we can match this new enlarged infinite set one-to-one with the set of natural numbers:

Any infinite set that can be matched in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers is called a countably infinite set, and the cardinality – or counting size – of a countably infinite set is denoted by

Any infinite set that can be matched in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers is called a countably infinite set, and the cardinality – or counting size – of a countably infinite set is denoted by .

“ green bottles, hanging on the wall,

green bottles, hanging on the wall,

If one green bottle should accidentally fall,

There’d be green bottles, hanging on the wall.

“ green bottles, hanging on the wall,

green bottles, hanging on the wall,

If two green battles should accidentally fall,

There’d be green bottles, hanging on the wall.

… …”

The one-to-one matching above does not preserve the order of all the elements. For example by our choice of where we placed the new element

but in the one-to-one correspondence, 1 is matched with 2,

is matched with 1, but 2 > 1.

If you think about it a bit you can see that no matter what we match with, we cannot preserve the order of the set

.

So the set cannot be matched in a one-to-one correspondence with the set

so as to preserve order.

One-to-one matchings that preserve order give us a new way of thinking about “How many?”

Infinite ordered sets that can be matched in a one-to-one order preserving way are said to have the same ordinality as and this ordinality is denoted by

.

From an order perspective the ordered set is bigger than the ordered set

, and it is natural to denote its ordinality by

.

On the other hand, if we think about what would be, it would be the ordinality of the set

and this set CAN be matched in a one-to-one order preserving way with

:

So .

So there you have it: the simplest “infinity plus one” is , but “one plus infinity” is still “infinity”:

.

Thanks to Georg Cantor for making this – and much more about infinite sets – clear to us.