When is an integer a square?

Posted by: Gary Ernest Davis on: November 30, 2010

This post came out of a conversation with James Tanton (@jamestanton) about squares of integers being exactly the integers not represented by rounding for

an integer (see here for background).

To say that rounding yields an integer

is to say that:

……………………………. (*)

Subtracting from the inequalities in (*) and squaring – as we can do and preserve the inequalities because the resulting left hand expression is positive – we get two quadratic inequalities for

.

After some consideration of these inequalities I was lead to consider the function .

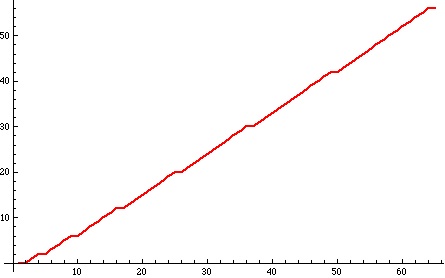

Below is a plot of this function for :

What is striking is that there are little steps in the graph.

What’s more striking is that these steps occur precisely when is a square.

In other words this graph, and much more numerical evidence, suggest that an integer is a square exactly when

.

I believe this, from the overwhelming numerical evidence, but I cannot yet see why.

Maybe someone else can?

Postscript

Nick Hobson (@quintic) provided a nice argument, in the comments below, that shows is a square exactly when

.

3 Responses to "When is an integer a square?"

Floor(k – √(k – ¼)) = Floor(k) – Floor(√(k – ¼)) – 1 = k – 1 – Floor(√(k – ¼)), for all k > 0, since √(k – ¼) is never an integer (because k – ¼ is never the square of an integer.)

So F(k+1) – F(k) = 1 – (Floor(√(k + ¾)) – Floor(√(k – ¼))), which is clearly equal to 1 unless k is a perfect square, when it equals 0.

Thanks Nick. That’s great.

November 30, 2010 at 5:20 pm

I don’t have an answer, but I noted this:

(k – 1/4k)^.5 is either a whole number or a whole number + .5 when k is 3 12 27 48 75 ….

where the second differences are all 6.

Not sure what (if anything) this adds to the solution